South Orange County schools dealing with major facilities needs

Aging elementary, middle and high school campuses in Dana Point and San Clemente are among several Capistrano Unified School District sites that require moderate to extensive facilities upgrades. Photo by Andrea Papagianis

By Andrea Papagianis and Jim Shilander

With Gov. Jerry Brown’s new Local Control Funding Program giving school districts statewide greater authority over funding and budgeting, districts are beginning to see the light at the end of the tunnel. And for the first time in years, the Capistrano Unified School District is discussing what can be done versus what couldn’t or had to be cut.

While returning to a full school calendar and reducing class sizes to previous levels remains at the forefront of discussion, the district is starting to address long-overdue maintenance needs in aging schools in south Orange County, from San Clemente to Aliso Viejo.

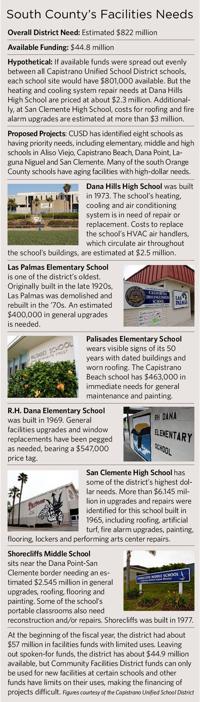

One year ago, outgoing Superintendent Joseph Farley said the district’s facilities needs were pushing toward $1 billion, highlighting a multi-year goal to complete upgrades and modernization efforts at several campuses. Needs were more narrowly defined in December as CUSD’s Board of Trustees readdressed a 2009 study by consultant WLC Architects where needed maintenance estimations topped out at more than $822 million across the district.

“The district has acknowledged many of our sites have needs,” district spokesman Marcus Walton said in an email. “Staff is addressing those needs as resources allow.”

While the district has needs everywhere, San Clemente and Dana Point are home to some of the oldest schools in the district, many of which pre-date the district’s formation in 1965. The increasing maintenance costs inherent in older buildings meant the economic downturn affected those buildings more, said Board of Trustees President John Alpay, who represents San Clemente.

“With many of CUSD’s oldest campuses located in the southern portion of the school district, San Clemente and Dana Point based facilities took a disproportionate hit,” Alpay said.

DPT_0221_SideBar

Eight aging schools from San Clemente to Aliso Viejo were identified by staff as having immediate essentials in need of repair, with costs totaling $13 million.

At San Clemente High School, those needs are estimated at $6.145 million for new roofing, fire alarm upgrades, artificial turf, flooring, painting and other general maintenance. For Dana Hills High School the heating, ventilation and air conditioning system needs replacing. Estimates place the project costs at $2.5 million.

Shorecliffs Middle School along with, Las Palmas, Palisades and R.H. Dana elementary schools also made the list, with combined repairs and general updates sitting near the $4 million mark. Those south county schools were all built prior to 1977, with Shorecliffs being the most recent addition.

But with an estimated $44.8 million in available facilities funding, the district has just 5 percent of monies required to cover all its needs. Projects at Dana Hills and San Clemente high schools recently went out to bid, but until numbers come back, district efforts to identify funding sources are a bit premature.

Gaining More Control

Brown’s reemphasis on local control during his State of the State speech in January made his position clear: Educational action should remain at the local level.

“With six million students, there is no way the state can micromanage teaching and learning in all the schools from El Centro to Eureka,” Brown said. “And we should not even try.”

In July, Brown signed sweeping legislation to overhaul the ways California’s public education system is funded, providing one of the biggest changes to K-12 funding in decades.

At the crux of Assembly Bill 97 was the Local Control Funding Program, aimed at providing districts serving higher-needs students—such as lower-income students and non-native English speakers—with increased funding. The law also gives local districts more control on how state funding is spent.

“Instead of prescriptive commands issued from headquarters here in Sacramento, more general goals have been established for each local school to attain, each in its own way,” Brown said in his speech. “This puts the responsibility where it has to be: in the classroom and at the local district.”

The increased flexibility comes with some stability in funds. In 2012, California voters approved Proposition 30, which allowed increases to both the state sales tax and on incomes greater than $250,000, which were earmarked for education funding. The proposition didn’t increase funding, but rather maintains funds by preventing further cuts to education.

The district is now considering its facility funding options. In a December 11 board presentation, staff suggested trustees consider issuing Certificates of Participation for upfront funding from Talega’s Community Facilities District.

But those funds are limited to new construction at school’s serving the community’s students.

The district originally considered Talega’s Mello-Roos funding as a source to mitigate San Clemente’s needs, but a recent refinancing of the fund will return an estimated $17 million to taxpayers in the area.

District staff also recommended looking at School Facility Improvement Districts for areas without CFDs. The funding comes from region-specific general obligation bonds that would pay off CFDs, providing funds for higher-needs schools. This option requires an additional viability analysis.

Additionally, district staff indicated that school facility bonds could make it to the 2014 ballot, giving voters the say into funding facility needs across the state.

But with specific-use limitations on various funds, the district has yet to earmark funds for projects and has not set construction timelines for when work could occur.

Getting Back to Basics

For CUSD, like many of its educational-counterpart agencies, 2008’s economic downturn meant severe budget cuts at the district level and steep downfalls in state and federal funding.

“Given the magnitude of these cuts, we witnessed a reduction in the school year, increase in class sizes, steep cuts in teacher and staff compensation and the evisceration of deferred maintenance,” Alpay said.

In 2009, class sizes were up to 31 students in elementary schools. The school year was reduced to 175 days during the 2011-2012 school year, but the district restored two additional days in 2013. Trustees expect to restore a full 180-day school year for 2014-2015. An agreement with the Capistrano Unified Education Association, signed in August, begins to bring down class sizes.

“Next year we will witness an increase in funding, and the trustees have made clear the first priorities will be on reducing class size and restoring the school calendar,” Alpay said. “The level of funding is simply not there to add facilities improvement to the list of immediate priorities; at least not yet.”

“Once funding is available, schools in dire need of facilities upgrades, San Clemente High School being a prominent example, will receive the extra attention they need and deserve,” Alpay said.

San Clemente High School. Photo by Brian Park

At a meeting last year, Alpay discussed the possibility of constructing a new pool at the high school. Alpay suggested upgraded facilities could serve as a selling point for parents, who could soon decide between sending their children to San Clemente or San Juan Hills high schools, once the La Pata gap between San Clemente and San Juan Capistrano is connected.

Since Talega residents helped pay for construction at San Juan Hills through a CFD, those students are given attendance priority but currently attend SCHS.

Members of the SCHS arts community have asked the district for a performing arts facility to replace the downtrodden Triton Center. The center is old and is badly in need of repairs. Mainly the ceiling needs fixing to cover a gaping hole.

Walton emphasized that the health and safety of students and staff is always a priority for the district. He added the district had consistently addressed facility issues using the resources available during the downturn.

The district estimated building a new theater at SCHS would cost $17.3 million. The number is based on recent construction of a similar facility at Capistrano Valley High School, accounting for subsequent increases in construction costs. New arts facilities at Capo Valley were paid with Mello-Roos funding from Mission Viejo and Aliso Viejo, along with grant funds.

Without those sources of funding, SCHS Principal Michael Halt is realistic about what can be done in the immediate future. When he toured the campus during his interview process last year, he understood needed improvements would take some time.

“It was clear the physical condition of the school was going to be a challenge,” Halt said.

However, the school’s staff has continued to make the best of the hand they’ve been dealt, by balancing teachers’ wants and the true needs of the school.

“They’re facing challenges that other teachers don’t have,” Halt said. “But they’re professionals and they’re doing the best job they can.” Halt added he felt confident talks with the district could help address some of San Clemente high’s needs.

Brian Park contributed to this report.